36% More Food, 69% More Learning: The Farm at RRU’s Remarkable Year

Discover how the Farm at RRU boosted food yield and expanded learning opportunities in its impactful 2024–25 growing season.

Discover how the Farm at RRU boosted food yield and expanded learning opportunities in its impactful 2024–25 growing season.

Visit Hatley Park’s hand-crafted Teahouse in the Japanese Gardens and have matcha tea prepared by Urasenke Tankōkai Victoria Association.

Horsetail is the nemesis of many gardeners. It’s also a common weed at the Royal Roads University Farm. But instead of seeing it as a source of frustration, Solara Goldwynn decided to learn more about this widely despised plant.

“I still pull it up, but now I also use it to make medicine and soak it to make compost tea, because it has all of these incredible benefits for our bodies and also for the land,” says Goldwynn, the farm and food systems lead at RRU.

Four years ago, she was busy with her family business Hatchet and Seed, transforming yards into food-growing spaces. She happened upon a YouTube video of RRU President Philip Steenkamp, talking about his desire to grow food on campus.

For Goldwynn, the message resonated, and she sent a pitch, right to the top. And as she got more involved in planning the farm, she started a Master of Arts in Environmental Education and Communication at RRU in tandem.

The new Giving Garden — a reimagined former 5.26 acre walled garden designed to support food security in the community — was an obvious place to build momentum and win support from stakeholders, funders and volunteers.

In less than a day, Goldwynn and team transformed a patch of lawn into a food garden, smothering the existing monoculture grass with cardboard and layering rich soil directly on top. Within a month, she harvested her first crop. By the first season’s end, the plot yielded more than 1,000 pounds of produce, all gifted to communities in need.

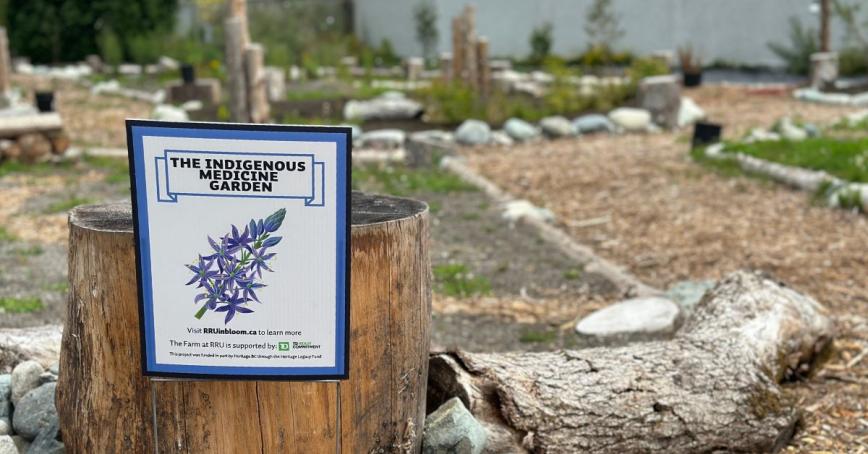

That was in 2022. Since then, the farm has expanded manyfold, to include an Indigenous Medicine Garden and soon, a large market garden that will sell fresh produce directly to the surrounding communities.

Beyond its bounty, the farm is also a space for community, and connection, says Goldwynn.

“I’ve had instances where adults have come to work on the farm, and they’ve never put their hands in the soil before. These spaces are transformative places, for people to connect to the land and tap into themselves.” – Solara Goldwynn

It’s been a whirlwind three years for Goldwynn, who relies on volunteers from Royal Roads and the community to help her with the work of the farm.

For her master’s major research project, she says she rooted deeply in place to better understand the land, the plants and her relationship with them. She sat on the farm and observed. She journaled and paid attention to several of the species growing there, researching not only their biological traits but also their histories, medicinal uses, folklore associations, and cultural significance. Included among them, the lowly horsetail.

Through these explorations, Goldwynn says she began to shift her perspective.

“How can we see horsetail as something other than a pernicious weed?” she pondered. “What are the plants trying to teach us about the environment and also about ourselves? What does listening to the stories of plants, fungi, and seeds teach us about sustainability and reciprocity?”

These are the types of questions she poses to RRU students, who come to learn at the farm.

Food gardens are useful for teaching broader concepts of sustainability and environmental education, she explains. “They are actually these incredibly rich libraries of human culture and ecosystems.”

Goldwynn crossed the stage at 2024 Fall Convocation. As for future plans, she hopes that grants and community fundraising will allow her to continue her work on the farm.

Learn more about the Master of Arts in Environmental Education and Communication program.

Learn more about the different ways you can support Goldwynn and her work.

The Farm at RRU is supported by TD Bank Group.

Hand-crafted Japanese teahouse at Hatley Park unveiled where formal tea ceremonies and special gatherings can occur.

Support the growth of the Indigenous Medicine Garden with a donation to the Vision in Bloom fund today.

Support the growth of the Indigenous Medicine Garden with a donation to the Vision in Bloom fund today.

An Indigenous medicine garden is much more than a space where traditional plants grow. The garden is also a classroom, the foundation of a curriculum, a reciprocal relationship, a revitalization of culture, an act of decolonization and a wealth of untapped potential.

The Indigenous Medicine Garden, the latest addition to the Farm at RRU, was designed by Kenneth Elliott, Cowichan Elder and ethno-botanist, and cultivated by Solara Goldwynn, farm & food systems lead for the Farm at RRU, as well as Elders and consultants from the Lands of the Lekwungen-speaking Peoples, the Songhees and Esquimalt Nations.

The space is a haven for Indigenous plants and medicines, and those who wish to learn from them. The Farm at RRU also hosts a Giving Garden and Market Garden and expands each year with support from donors and volunteers. Goldwynn has big dreams for the space, and for the Indigenous Medicine Garden in particular.

As farm & food systems lead for the Farm at RRU, Solara Goldwynn looks after the gardens and coordinates volunteer groups, tours and events in the Farm.

As farm & food systems lead for the Farm at RRU, Solara Goldwynn looks after the gardens and coordinates volunteer groups, tours and events in the Farm.She wants to create a place where people can interact with plants, see what Indigenous plants look like and learn about what their uses are. “And to go outside of the walled garden, to the campus and see them there… And [for community members] to learn about the cultural practices and medicinal values of these plants.

“I have a lot of hope that there will be people in this space learning and being able to feel connection to the land here,” she says.

Russell Johnston, director of Indigenous Education, and Jasmine Dionne, instructional designer at Royal Roads University, have a similar vision — but one that involves a diploma. Their team is designing a new Indigenous Studies diploma program with Land-based learning at its foundation. When the program is ready, the Indigenous Medicine Garden will serve as a living classroom.

Land-based learning will be foundational for the future Indigenous Studies diploma program at RRU, and much of that learning will take place in the Indigenous Medicine Garden.

Land-based learning will be foundational for the future Indigenous Studies diploma program at RRU, and much of that learning will take place in the Indigenous Medicine Garden.“The goal is to create an engaging Land-based program where students can see themselves reflected in the coursework, the curriculum, the faculty,” says Johnston. “[We’re] excited about this opportunity to build something that can serve the people we have a responsibility to — the original caretakers of these Lands.”

Some of the program’s learning outcomes, shares Dionne, are: “investigating Indigenous approaches to ethics and governance; analyzing historical and contemporary assertions of Indigenous sovereignty, self-determination and sustainability; question and build on concepts of responsibility, community development, governance and sustainability; understand the significance of Traditional Ecological Knowledge and explain the relationship between Land and indigeneity within Indigenous communities.”

Aside from its academic potential, Johnston and Dionne hope the garden can help the university community grow and meet its commitments to Indigenous Peoples.

To explain the connection between land-based learning and decolonization, Dionne refers to the words of Eve Tuck, professor of Indigenous Studies at the NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development: “Land-based pedagogies are essential interventions against biopolitics, because it puts Indigenous peoples on the Land, it feeds them, it teaches them, and it displaces what settler project was there prior.”

“I think it allows [community members] the opportunity to ask more questions about colonialism and displacement and what their relationship to Land should be going forward,” says Dionne. “It’s one of the best ways for the institution to grow and it can do that by supporting students’ access to the garden.”

RRU community members came together for the initial planting of the Indigenous Medicine Garden, and the space relies on volunteer involvement from students, staff and faculty.

RRU community members came together for the initial planting of the Indigenous Medicine Garden, and the space relies on volunteer involvement from students, staff and faculty.The garden gives Indigenous students the opportunity to access what is theirs, adds Johnston. “Those teachings, those medicines, those things belong to them. We’re providing a space for them to regain access to the teachings and everything those relationships can provide.”

The Indigenous Education team expects the relationships between students and Land will be reciprocal, with native plants and medicines finally given a place to thrive.

“It’s like giving a stage back to the Land and saying: ‘here’s an opportunity for you to share with us what you think is appropriate,’” says Johnston. “Not only do the students get to learn, but we’re also providing an opportunity for the traditional plants and medicines to have their voice and relationships re-established, because those have also been severed through colonization and through the shift of these spaces.

The Indigenous Medicine Garden is filled with plants native to the area, like the Pacific Crab Apple.

The Indigenous Medicine Garden is filled with plants native to the area, like the Pacific Crab Apple.“And especially here [on the Royal Roads campus], the lagoon has been a classroom since time immemorial. We’re just resurfacing, re-establishing what this Land has always done,” he says.

Referencing a paper from Bang et al., Dionne shares that most people perceive the world as “I am, and therefore place is,” whereas projects like the Indigenous Medicine Garden can help shift perspectives to “Land is, therefore we are,” which has ecological, political, and cultural impacts.

The Farm at RRU is supported by TD Bank Group.

Alum Eve Martin and her spouse Paul help bring teahouse within the 100-year old Japanese gardens to life.

It’s been a BIG year at the Farm at RRU! What was once a fallow, underused lawn is being transformed into a 5.26-acre edible and medicinal greenspace.

In honour of their mother who loved peace and flowers, a Victoria family dedicated a bench to her in the Royal Roads Italian garden.

The Farm at RRU helps address food insecurity in our region. RRU professors are helping communities like ours research options for stable food sources. Below is one example of our faculty sharing their expertise with other British Columbians.

The future is uncertain, so how do you plan for it? For example, what would you do if your local grocery store suddenly had a shortage of produce? What if that shortage continued for months?

Assistant Professor and Canada Research Chair in Climate Change, Biodiversity and Sustainability Rob Newell and collaborator Professor Leslie King aim to answer these questions.

The duo received a $25,000 Partnership Engage Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to work on the project Food Systems Scenarios in an Uncertain Future.

Many Canadians already experience food insecurity. That trend is likely to continue rising amid challenges such as extreme weather due to climate change, the knock-on effects of another global pandemic or supply chain issues caused by conflicts in other parts of the world. All of these factors affect governance and food security.

Partnering with the Community Connections (Revelstoke) Society (CCRS), Newell and King will work with community stakeholders in Revelstoke, BC to identify a future scenario that represents an equitable and resilient local food system – the ‘dream scenario’ if you will. Once identified, they will then explore alternative scenarios that respond to external pressures and shocks — such as extreme effects of climate change or impacts from global conflicts. The final stage of their research will be to identify interventions needed to achieve the dream scenario and chart the actions required to make progress toward the future ideal.

Local government, non-government organizations, community organizations and other stakeholders will take part in a series of workshops to help researchers identify the elements needed for an equitable and resilient local food system. One way they’ll examine possible scenarios and experience what food futures could look like in Revelstoke is by using an online visualization tool developed using 3D game-development software.

Users of the visualization tool can navigate various scenarios through the first-person perspective, and walk-through, for example, a virtual community farm. Their 3D explorations might reveal the need to build in more plant shelters to adapt to increases in extreme heat events. Other examinations of food supply would include the need to consider opportunities for people to have traditional or culturally preferred foods.

“In some ways, you’re dealing with these multiverse elements,” Newell says, the project’s principal investigator. “But that’s just reality. Certain disturbances, certain trends are going to shape where we go and what the world looks like.”

The work is the continuation of another research project with CCRS, says Newell, whose Canada Research Chair work carries a focus on improving social justice and equity in local food systems through long-term planning that looks ahead all the way to the year 2100.

“Our future deals with a lot of uncertainty. Given world trends, how might this scenario change, how might it look different? What sort of interventions, what sort of strategies do we need to have a resilient, livable food future?

“It’s a new way of being able to do scenario analysis that doesn’t keep you so locked and fixated on one particular future and helps you understand that there are multiple pathways, and it’s good to be prepared for multiple futures.”

Our recently established Indigenous Medicine Garden is now home to dozens of native plants, thanks to the guidance of Indigenous Elders, ethnobotanists, staff, volunteers and donors.

Watch the first planting session of many to come below: